When gamers talk about Earthbound, it’s usually about the quirky nature of the game and how it’s a refreshingly unique take on the JRPG. It definitely exudes charm in its eclectic interpretation of American culture from the vision of writer and director, Shigesato Itoi. But there’s one scene that resonates with me and made Earthbound more subversive, and impactful, than I’d been expecting.

It revolves around a place called the Happy Happy Village.

Some People Just Want To Paint The World Blue

Earthbound’s story invokes an alternate version of America where a bubble gum chewing monkey, time traveling aliens, and a psychedelic city of illusion called Moonside, are part of everyday life. Even the Loch Ness in the form of Tessie makes a cameo, giving you a ride like it were the local ferry.

The whimsical charm comes from contrasting the mundane with the fantastic, emphasizing the oddness of suburbia by skewing the edges with surreal enemies like a “Worthless Protoplasm,” “Plague Rat of Doom,” and a floating mouth called “Kiss of Death.” Playing as kids, you’d think adults would be the source of reason, or at least safety. To the contrary, regular adults like the “Unassuming Local Guy,” “Cranky Lady,” and “New Age Retro Hippie” are your enemies, attacking you mercilessly. Decades before Persona 5 had your band of outlaws face off against corrupted adults, Earthbound had you doing the same. Only with an idyllic 50s aesthetic that seems a paean to a bygone era. Dig a little deeper into the era, though, and Earthbound will reveal that most of that idealism is just a veneer that can be scratched away at.

The game has its own “kidnapped damsel in distress” trope, but like the rest of the game, with a strangely psychic twist. Ness has to rescue a preschool student, Paula, who’s been kidnapped by adults. You discover this after she uses telepathy to contact you through your dreams. I always found it interesting that of all the people she could contact, it was you, a strange kid she didn’t know. Even Ness rarely relies on adults, though he does have nostalgic bouts where he has to call his parents to ward off homesickness.

Once you enter into the Happy Happy Village to find Paula, eerie music wafts through the “happy” streets. All the houses are painted a dank blue. The first citizen you encounter informs you, “One day, Mr. Carpainter received a revelation. He now speaks the real truth.”

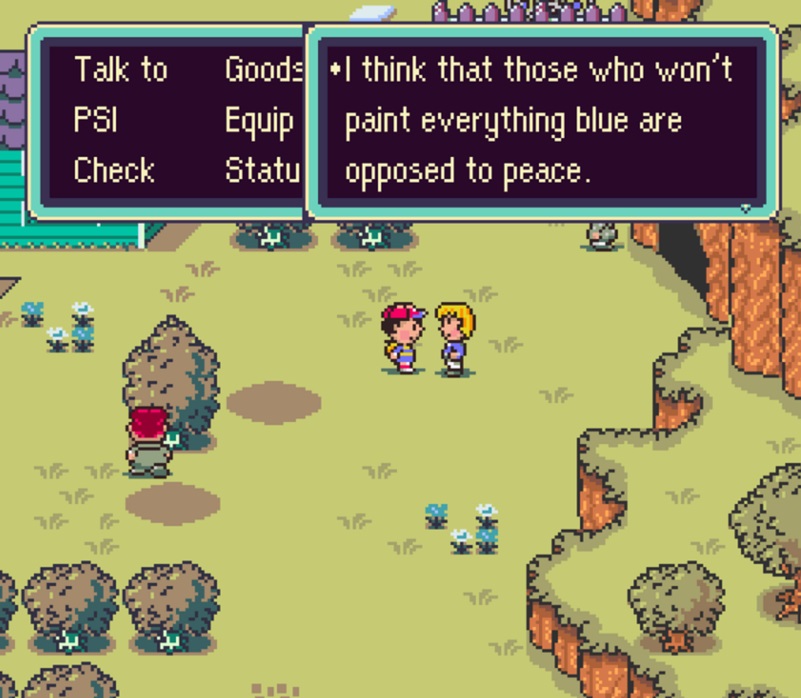

I had no idea what the real truth was, but I was forced to make a donation/offering for being a tourist. Many of the denizens I met insisted that everything ought to be painted blue and one person bluntly informed me/Ness: “I think that those who won’t paint everything blue are opposed to peace. I want them all to listen, even if it requires kicking their butts.”

Even with the limited 2D sprites, I could feel her maniacal absolutism, justified, in her mind at least, by the desire to protect and uphold the social welfare of the village. The houses are blue, the flowers are blue, the tree have their bark shaded blue, and even the cow is painted blue. It’s a blue storm of blue hues and blue vigor. People even have to chant “blue… blue…” before bedtime, invading your dreams with blue.

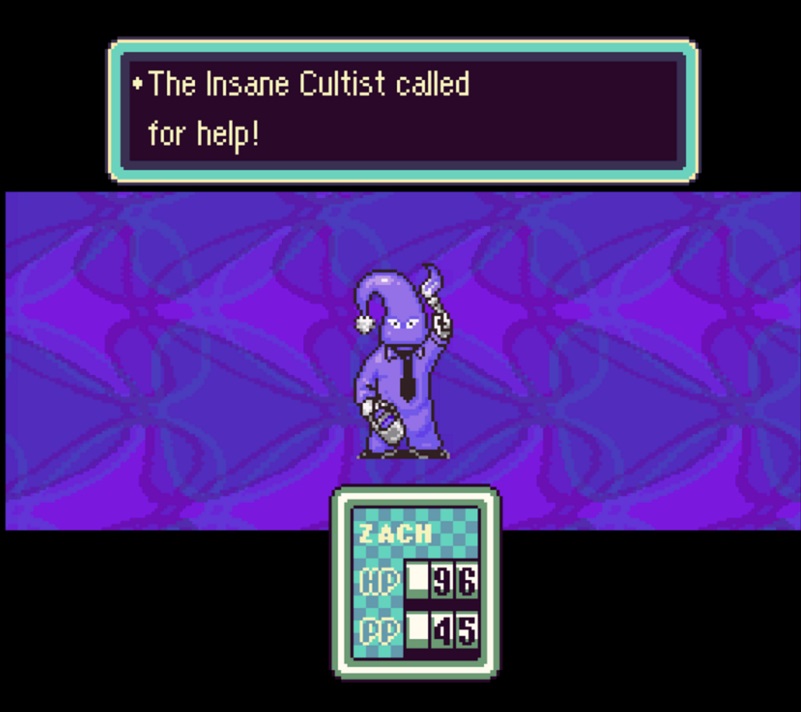

The most unnerving part are the bizarre “insane cultists” who roam the streets, maintaining their strict order. Their blue robes resemble Ku Klux Klan members and they march with violent zeal. In the localization, cotton balls were added to the tips of their hats and the HH for Happy Happy was removed in order to differentiate them from the KKK. They’re still terrifying. The moment they see you, they rush and attack using their paint brushes. Even though Ness is wearing blue shorts and a striped shirt where half is blue, he’s still not blue enough for them.

Interestingly, the first thing most HH members do in battle is call for help. More members arrive, despite the fact that they’re teaming up against a kid. These cultists will rarely fight alone and I wondered if it was a commentary on the nature of fear-based cults/bluist groups, dependent, both physically and ideologically, on each other to prop themselves up.

The Real Truth

The Happy Happyists don’t just want to paint the world blue. Their sinister scheming involves making the young girl, Paula, their high priestess. It’s up to Ness to retrieve the key from the cult leader, John Carpainter. Once you find Paula in her prison cell, she gives you a Franklin badge that makes you impervious to the lightning attacks Carpainter unleashes.

Nothing like the ingenuity of kids to defeat evil psychic powers.

You enter the Happy Happy headquarters and find what is one of the biggest conglomerations of 16-bit character sprites I’d ever seen. There is a sea of blue Happy Happy members, worshiping, philosophizing, and trying to fit in. “Happiness” they claim they’re spreading, when it’s actually a conformism that’s made even more fearsome by their blind devotion.

I’ve written in previous articles about my fears of moral absolutism and how much of it has roots in good intentions. I’ve had friends who were members of religions considered cults and seen firsthand the pain they can bring to those around them.

In Earthbound, when you do face Carpainter, he offers you a chance to help change the world “into a happy and peaceful society” by becoming his right-hand assistant (I don’t know if this was a nod to the original Dragon Quest, but it’s a neat option). Again, he fervently believes in what he’s doing. If you refuse, he strikes you with lightning, but even if you accept, he lambastes you.

Earthbound’s combat is a pachinko inspired marathon that alternates with a psychic induced sprint. Turn-based, it incorporates innovations like a running odometer for a health bar and the ability to skip battles against overpowered enemies to streamline the experience. Weaker foes will even run away from you (a mechanic that Persona 3 also incorporated). Mental powers stand in for magic, and common household items like frying pans and baseball bats are the weapons of choice for the young band. In the fight against evil, anything can be a weapon.

The battle against Carpainter is not difficult, though surreal, as halos of blue paint emanate from him like a holy aura. After his defeat, Carpainter expresses remorse and blames the Mani Mani Statue for his actions.

The Happy Happy members dissipate (there’s only three left). The remaining ones have vanished. The houses go back to their normal color and people apologize to you. But their sincerity seems questionable and a little too convenient considering their leader took a beating at your hands. Just as the graphics are rooted in the mundane, then get twisted as they reveal their true corruption, I couldn’t help but feel that the evils still existed as an undercurrent through the entire valley.

One of Earthbound’s best features is to convey the absurdities of existence through the eyes of kids. The game reminded me that the world is a strange place and sometimes, an individual with a little bit of bravery standing up to insane cultists (or any number of “isms” you can think of) is the only way to change a society (although psychic energy and a trusty bat go a long way in helping).

There’s many reasons the game is considered an underappreciated classic. In this case, it’s the relatability of the experience, rather than the strangeness of it, that made it so striking.